Paul and Brett's Alpha

Prisoners of Demography

We are living in uncertain times and it is surely beyond doubt that we are going to face below trend levels of economic growth in the short term, owing to the various geo-political and macro-economic headwinds that COVID-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have triggered. Overcoming these will be made harder by the need to comply with rules in respect of the transition to renewable energy and net zero. This shorter-term uncertainty is reflected in febrile market sentiment.

If you are reading this factsheet, then we can reasonably assume you are either: i) a current shareholder in the Trust, ii) someone considering investing in the Trust, iii) an interested observer of the healthcare sector, or, iv) someone else who works in finance.

If you fall into one of the first two categories, then you are likely to be seeking to preserve and grow your wealth and/or maintain an income through retirement. Last month’s missive raised the question of persistent inflation coming back into the investment decision-making process. Unless you are committed to analysing and trading your portfolio on a daily basis like an investment professional, achieving either of the previously described aims requires you to select investments that you are confident will be able to easily outpace inflation.

This, in turn, requires investments in companies that can outgrow their industries or that are in segments where growth above inflation seems assured. Never has achieving these aims felt harder than it does today, with so many industries being disrupted and, at the same time, so many of the putative disrupters turning out not to be the solution (cf. last month’s comments on Tesla and Beyond Meat).

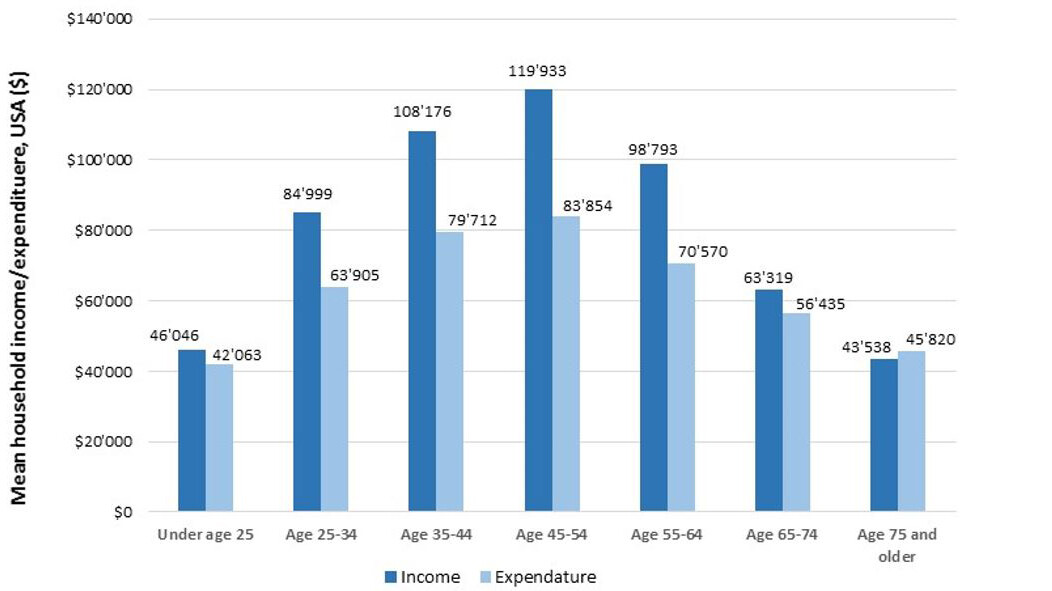

The investment waters are made even murkier by demography. The population in the majority of developed markets is ageing rapidly. Whilst they are typically the most “asset rich” demographic segment (due to a lifetime of work and consequential asset accumulation), older people generally consume less of everything that is discretionary (see Figure 5 below). They are more risk-averse, have a furnished home, and any children have long since left the nest. Their income is usually lower than it was when they were working and they tend to be conservative in their adoption of new technologies.

In contrast, those same demographic trends suggest that the “yoof” market will barely grow in population terms and the next generation is being inculcated with the message that consumption is destroying the planet. They are going to be a much harder sell for advertising gurus than us “Gen X’s” and “Boomers” were.

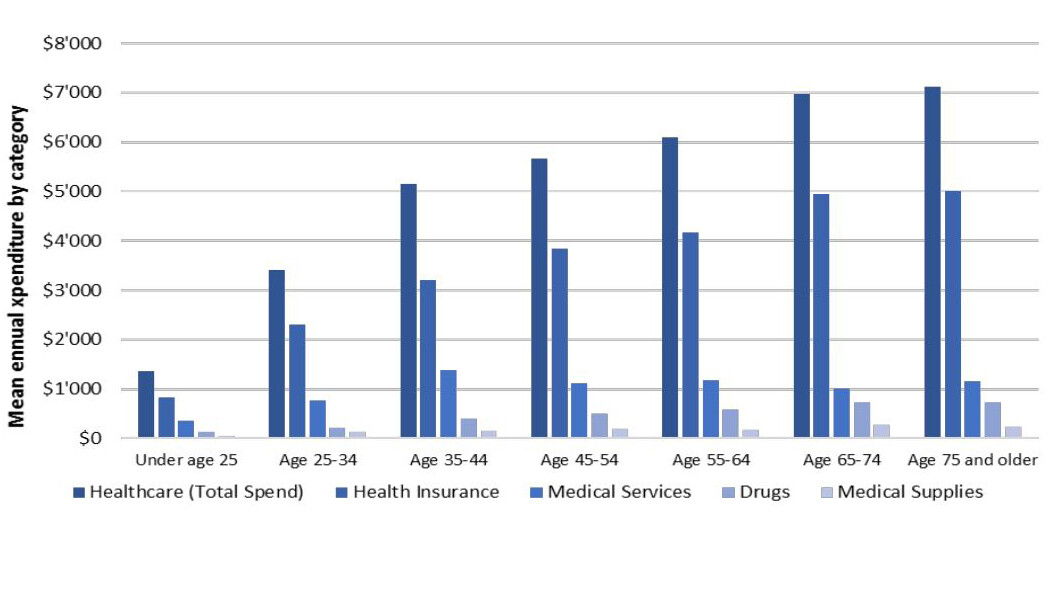

The elderly do consume two things at a much higher rate than the rest of the population; welfare (mainly in the form of pension receipts, but also some disability payments) and healthcare (Figure 6 illustrates healthcare consumption by age group in the US; the current average is $5,450 per capita per annum).

Here in the UK, 22% of UK tax receipts are currently spent on healthcare and around 40% of that (i.e. 8.4% of the total) goes to caring for the over 65s. Retirees receive another 10% in state pension payments. Central resources (i.e. those not directed to any specific group of the population - transport, defence, public order and administration, including debt interest) account for 30% of expenditures).

If we exclude these central costs, spending on the over 65s account for about 28% of direct government expenditure (they account for 19% of the population), which does not seem overly problematic, although one must remember that the UK runs a primary budget deficit, spending c£125bn per annum more than it receives in taxes (currently equivalent to 5.4% of GDP and one of the highest peacetime figures in the nation’s history).

The primary budget deficit is an important topic in and of itself, but we have covered that before. In many ways, what we are spending now is not the issue, it is what we need to spend in the future…

The future isn’t garlic bread…

We never set out to frighten anyone with the content of these missives, but any reasonably informed analysis of the ultimate consequences of current demographic trends are genuinely quite worrisome if you are in one of two groups: those expecting to pay taxes for many more years to come and those expecting to receive social welfare and related services in the future. Generally speaking, that covers all of us.

How does one begin to think about the consequences of current demographic trends? The future for most developed countries probably looks like Japan, which leads the advanced economy group in population ageing (Monaco is actually the ‘oldest’ country, but its residents don’t have to worry about the costs of, well, anything really).

In Japan, 29% of the population is now over 65, compared to 18% in 2000. The UK passed the 18% level only in 2016, so we can think of ourselves as being 15 or so years behind Japan. Japan’s healthcare expenditure per capita currently stands at around US$4,400 and has grown at an impressively low compound rate of 2.5% since 2000. This is lower than the rate of growth of the population over 65 (+4.3%), but still much faster than GDP (+0.6% over the same period; it has grown very slowly due to the aforementioned challenges posed by such a demographic shift).

As a consequence, even today with such an aged population, healthcare expenditure accounts for “only” 10.7% of GDP. This is largely due to two factors; a very healthy lifestyle for the average Japanese person compared to a typical westerner (as evidenced by longer life expectancy) and aggressive cost containment by the government.

In Japan, fees for medical services, products, and pharmaceuticals delivered by almost all healthcare providers are dictated by a national fee schedule set by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. These fees are reviewed on a bi-yearly basis and are often volume-weighted. Simply put, the more successful your product or service, the more price you are expected to give up.

So far, so not-very-scary. At first glance, Japan appears to have manged its demographic transition and consequential economic slowdown well. Healthcare spending has not gotten out of hand and public services have been sustained, even against a background of low economic growth.

There are two issues however: i) who pays and ii) Japan has not yet crested its ageing wave from a cost perspective. Whilst the population over 65 in total is expected to fall in the coming years (from 51.2m in 2021 to 50.4m in 2030), those who do not die will be older and more expensive to look after. From an administrative point of view, the government is liable for all expenses once people are aged 75 and above and the tax implications of the gradual transition to funding this are significant, especially when the working age population is shrinking so rapidly.

Japan will cross a Rubicon in 2025, when there will be more retirees aged 75+ than below. At the same time, the falling birth rate (another widely shared problem across developed economies) means that the “working age population” (which for some reason still gets defined internationally as aged 15-64) will decline by 1.9m or 2.6%.

What does this mean? Higher taxes. In turn, those taxes will slow economic growth, which is already anaemic. Lest we forget, this is simply the beginning of Japan’s dependency and spending nightmare. The population will go on shrinking and the dependency ratio will go on rising for many decades to come. Beyond 2030, the working age population is expected to halve 10 years before the over 65 population does (2105 vs. 2115, according to the OECD, although any projection so far in the future is almost certain to be wrong).

Even if the figures are on the pessimistic side, this is going to be very expensive and create a huge fiscal drag. The culmination of this dismal demographic direction was evident in comments from Japan’s Prime Minister Fumio Kushida, who said a fortnight ago that “Japan is standing on the verge of whether we can continue to function as a society.” Serious sentiments indeed.

At this point, someone might optimistically suggest all will be well because Japan will introduce robots to do all the extra work that a smaller human population needs to do. This is a fine idea, but probably not a realistic hope in the short-to-medium term. The more logical solution is mass immigration (of skilled people) to address the dependency ratio imbalance and compensate for the lower birth rate. However, some societies (especially Japan) are not yet ready to accept this is the inevitable reality that they must confront. Selling mass immigration is not going to be easy.

The DSS is paying me wages and it won't cost you a penny

Let us bring the discussion back to our Sceptred Isle. Our own analyses suggest that the UK is uniquely poorly placed to deal with these various challenges. The first reason is the base level of wellness – we are not, as the Vapors sang, ‘turning Japanese’. Indeed, when our European cousins refer to us as the “sick man of Europe” they do so with good reason. All of the data that follows is population-level averages, so please don’t take it to heart: Demography is not personal destiny.

Our government knows that we face a crushing dependency ratio problem and its response begins with the logical conclusion that the pension age must be raised again. The latest proposal is to raise the pension age from 65 to 68 for those aged 54 or younger today.

In the fantasy world of the Treasury’s Excel spreadsheet, this will help to curtail pension costs and also keep people working for longer, raising tax revenues. As with most ideas from this etiolated administration, the wheel comes off as soon as the rubber hits the road:

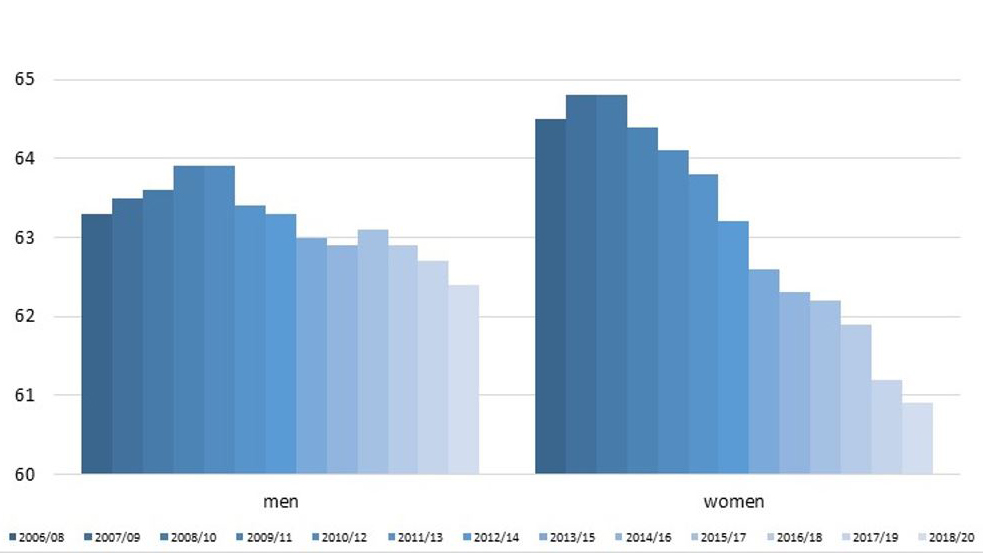

The keen-eyed will note that this chart’s axis is not labelled, which is intentional to make the reader focus on what it shows: a declining trend over time after about 2011. Now that we have your attention, this is UK government data projecting how many years of disability free life people in the UK can expect from birth. This is defined as the number of years lived without a self-reported long-lasting physical or mental health condition that limits daily activities.

Firstly, its declining, which is clearly a (very) bad thing and secondly, it's already well below 68! What this suggests is that, on average, people living in the UK can expect to spend a growing proportion of their lives with a life-limiting condition and the primary driver of this is a rising incidence of chronic mucoskeletal conditions, which are the ones most likely to cause you to quit the workforce.

This dataset was produced in 2021 and does not yet cover the impact of the pandemic. Given Long COVID and the likely related global trend of elevated excess mortality in the 40+ age group that we are seeing, it seems logical to us to conclude that a data series running through to today would look even worse.

We think some early evidence of this is apparent in declining workforce participation (i.e. the percentage of the 16-64 age group that is defined as economically inactive). In December 2019, this was 20.1% and at the end of 2022 it was 21.3%. Over this time, the number of people enrolled in full-time education has remained constant at c4.1m. The UK charity AgeUK estimates 3.5m people aged 50-64 have left the workforce, many due to ill health.

Those who are no longer actively seeking work cannot claim ‘Jobseekers Allowance’ and thus are lost to many official statistics such as being counted as unemployed (Per ONS: “anybody who is not in employment.. has actively sought work in the last 4 weeks and is available to start work in the next 2 weeks, or has found a job and is waiting to start in the next 2 weeks, is considered to be unemployed”).

As discussed in previous factsheets, there has been a phenomenon of over 50s in particular dropping out of the workforce. The truth of the matter is that we do not actually have robust data on how many such people we have in the UK and thus if their numbers are rising, falling or staying the same. Based on the available evidence, it appears to us that the numbers are rising.

Some might be early retirees who have quit at 55 or who can afford to bridge the gap until their pension kicks in from their private wealth (inflation must be hurting this group; perhaps there are people who will now need to “unretire”). Many of the others are too ill to work themselves or are full-time carers for someone else who is chronically ill.

Coming back to the economy and growth – asking people to work longer is fine as an idea, but it does not feel to us like it will play out as intended. Instead of pension payments, the government may simply end up paying out even more in long-term disability, negating the savings. This means that the remaining employees will have to pay even more tax. When it comes to driving the economy forward, it is not the size of the population that matters, it’s the size of the working population.

There’s no place like home

From time-to-time in days of yore, someone somewhere would describe the NHS as ‘the envy of the world’ or ‘the world’s best healthcare system’. 2014 springs to mind as the last such occasion, but we don’t think this has ever been objectively true in our working lifetimes. It is a pitiful story of managed decline, save for a brief uptick in the Blair/Brown years (we’ll come back to that; their domestic legacy is certainly up for some debate).

However, this edition of the factsheet is not really a discussion of the healthcare system per se; it’s about economic growth, so we won’t dwell on debunking fallacious commentary beyond observing two things: i) you won’t find any headlines like that today, and ii) if our 70-year old NHS system is so great, why is it still also unique across the world? Surely if its munificence were so compelling, it would have been copied over and over by now? This observation exists in parallel with the increasingly apposite ‘sick man of Europe’ trope.

Let us not get bogged down in the many and various travails of this benighted service and focus on the economic consequences of demography. As noted previously, we are not Japan. We might be 15 years or more behind them on the demographic curve, but we had almost caught up with them in 2019 on healthcare spending per capita (US$4,350) and as a proportion of GDP (10.2%). As readers will be all too aware, economic growth has been slow since and the NHS has seen a major cash injection, so we think it safe to assume that we are now past Japan on both measures (we focus on 2019 to avoid any pandemic distortions to inter-country comparisons).

There is worse news to come. Firstly, we have our own demographic wall of worry to climb. Between 2021 and 2030, the population over 65 is expected to grow by c1.1m people. Over the same period, the working age population will increase by ~0.7m. That does not sound too problematic, except the age skew on healthcare expenditure by age group in the UK looks much steeper than it does in other countries because of our integrated healthcare system and the vagaries of our accounting for that expenditure.

In the early adult years, UK citizens are seen to “spend” very little, whereas other countries that mandate the young and healthy to buy insurance create an effective smoothing of the age-to-cost curve, because that insurance is still health spending (cf. Figure 6 previously in the US for example). There are no hypothecated taxes in the UK and so the idea that NI contributions fund healthcare and pensions is a myth.

Thus, whilst healthcare cost for the over 65s is around 1.3x the population-level mean in the US, it is more like 2x in the UK. We also have a much higher background level of annual healthcare cost inflation than other countries. You can argue how much is due to historical under-investment and how much is due to a ‘sicker’ population, but the outlook for spending growth is far worse (4%+) than that of Japan or even the OECD average (~3%). This is before one considers the consequences of the NHS staffing up to its desired capacity and potentially meeting the wage demands of striking doctors and nurses and so on.

What does this mean? Our analysis, which we think is conservative because it does not seek to address the NHS’ many shortcomings, predicts spending on the over 65 group will grow by $100bn (£81bn) by 2030. The total NHS budget today is £180bn (including £33bn of ‘one -off’ budget increases announced since 2018). Even so, £81bn would represent a massive increase (equivalent to the base budget growing 4.8% per annum) and, lest we forget, it does not include the additional costs of modernisation or of meeting the needs of the under 65s, which will also rise due to inflation and healthcare expansion (new treatments, etc. etc.).

There are a number of projections you can find from third parties such as the Nuffield Foundation, Institute for Fiscal Studies, Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), etc. and you will find similar projections that take the budget toward the £250-300bn range by 2030-2032. Generally speaking, the more “official” they are, the lower they are. Make of that what you will, but bear in mind the government keeps having to provide top-up funding (that £33bn since 2018), which suggests strongly to us that its own projections for healthcare spending tend to be wrong.

Indeed, if you look at the healthcare spending projections on the OBR website, you will find this caveat: “policy risks from NHS spending could well still remain to the upside”. As evidence for this continued pattern of under-estimation, the 2030 budget forecast published in a special report by Lord Darzi for the May administration in 2018 (just before one of those ‘one off’ budget increases was announced) was £173bn, which is lower than the current budget in 2023.

Also bear in mind that many of our problems with the NHS today derive from our broken social care system and there isn’t even a plan to fix that, never mind a budget. A residential place in a private high quality dementia care facility costs more than £1,000 per week. That will soon eat through your savings (if you have any). Not fixing national social care provision is just another stealth tax on the “wealthy” (actually anyone with savings of £32,500 currently; this is rising to £100,000 in 2025 and includes the value of your own home, which you are expected to sell or use equity release to fund care).

Assuming the needs of the elderly are met (and that is a huge assumption that is not at all justified by current conditions), somebody has to pay for it. One way or the other, that somebody is you (and us too, and your children and grandchildren). That’s a LOT of extra tax.

In all probability, you will pay all this additional tax and still the service will degrade, so you will also spend increasingly more on private healthcare (if you can afford it) and, likely as not, private social care for your loved ones to give them dignity in their final years. Heads you lose, tails you still lose.

All this to think about and we are not even trying to consider fixing the roads, the schools, the trains, the energy grid, flood defence, the armed forces, etc. etc. Even if this all gets addressed, Britain will still be broken.

We've got to grab the cow by the horns and pull together

We face a massive bill. One would hope that an acceleration of economic growth could be utilised to moderate the pain of meeting these costs. That was the dream of Liz Truss and her now legendary “mini budget”. There’s nothing wrong with dreaming, but we have to live in the real world and here again we have some major issues.

The first is Britain’s terrible productivity growth in recent decades. Since the 1980s, productivity has improved at a rate somewhere between one fifth to one quarter of that seen in France, Germany and the United States. Why is this?

Everyone will have a theory behind low productivity growth, ours is that there has always been an easier option. Productivity growth was comparable to peers up to the 1970s. At the end of this period, the country was a mess, inflation was rampant and the unions ruined everything (sound familiar?) and so one had to box clever to make profits grow.

Then came Mrs T and deregulation fuelled massive growth and lower taxes. If you were a CEO, the sun came up in the morning and your profits grew. It was almost that simple. Focus on the opportunities at the revenue line, don’t worry about the P&L.

Meanwhile, people got better educated, IT tools went mainstream and women joined the workforce in ever greater numbers – these factors represented ‘low hanging fruit’ to drive the economy forward. Then there was off-shoring. Things began to slow down as the new millennium dawned, but then came ‘St. Tony’ and Gordon the genius; he who claimed to have abolished ‘boom and bust’ (they were in power via Faustian pact from 1997 to 2010).

The Blair government allowed mass immigration from eastern Europe at a faster rate than other European countries, making the UK a destination of choice for those now able to cross the fallen iron curtain. This arguably drove down wage inflation for a generation. The Blair government also introduced working tax credits and child tax credits (both in 2003) and a minimum wage (1998), although the latter is widely recognised to have been set too low and to have risen too slowly in ‘real’ terms (hence the need to also describe a “living wage”, which has always been higher).

In many ways, one could argue these few decisions set in motion many of the problems that we have to deal with today. Resentment over unskilled labour ‘competing with indigenous workers’ arguably contributed significantly to support for Brexit and the consequential disappearance of that cheap imported labour, which subsequently exacerbated hiring shortages and wage inflation in the post-pandemic period (e.g. HGV driver wages, which grew below inflation in the 2000-2019 period and have increased hugely subsequently and are expect to continue to rise over the next two years).

The changes to the benefits system and legal minimum wage, whilst well intended, have perpetuated a system whereby employers (often large and profitable corporations) pay unskilled people at a rate that is unliveable and the taxpayer funds some of the difference with top-ups! When you write it down in black and white, it becomes patently obvious this situation is utterly absurd.

If the minimum wage were set at an appropriate level, there would be much less need for ‘in work benefits’ and, in all probability, the population would be healthier and see a higher workforce participation rate. Higher wages would also incentivise employers to invest more in productivity improvements which have been shown to raise economic growth and living standards.

One could counter that raising the minimum wage could risk a significant increase unemployment or deter job growth in the wider economy as companies invest in tools rather than people. However, there is scant evidence to support this theory from those countries that have introduced it or from the variation across states in the US (lowest rate is Alabama at $7.25/hour and the highest is California at $15/hour for most businesses). The best analogy is that of a rising tide lifting all ships.

The second problem is demography: our working age population is barely growing. Higher taxes when combined with a stagnant working population are a recipe for pedestrian economic growth.

The third problem, as discussed in a previous missive, is that we run a primary budget deficit. Britain is already living beyond its means and is going to have to keep finding people to buy its bonds to fund all of this. That will get more difficult over time, further exacerbating tax rates as we will need to cover a growing interest rate bill (£43bn in 2022).

Some countries will fare much better than us. Those with large domestic markets, energy independence and low levels of regulation that allow innovation and flexibility around labour. A culturally open attitude toward immigration to blunt the dependency ratio progression is also an asset. Where will you find all of these things wrapped up in a neat little parcel? America.

Even with its dysfunctional politics and culture wars, historical immigration has helped to flatten the demographic curve and thus the dependency ratio in the US is forecast to be lower in 2050 than it is today in the UK. That is not to say that the US does not also face a tax and spending dilemma, merely that it looks to be a more manageable one than our own, and this should support higher economic growth.

Thanks for sharing. No, really, thanks

For those of you still reading, you are probably wondering why we have elected to share this incredibly depressing outlook with you. There’s enough bad stuff going on in the world right now as it is; do you really need to be reminded that things could get a whole lot worse before they eventually start to get better, especially here in the UK?

Does it need to be repeated that we are reliant on a bunch of wannabe-famous intellectual lightweights to get us out of this? Those in power have been ignoring all this data in favour of short-term boosterism for decades; why will they suddenly try and address the problems now?

We have laid all this out to highlight the importance of having an investment portfolio constructed to deliver long-term, above inflation growth. Where are you most obviously going to find that? As noted previously, international healthcare and the clean energy transition seem the obvious plays. The former is driven by demographic inevitabilities, the latter by regulation and growing consumer pressure, as the reality of climate change has become a mainstream position.

The healthcare industry will face challenges too – society will not keep opening its wallet and thus productivity improvements are desperately needed. We know the current approach does not scale well and it is now far too late to try and bridge the human labour shortfall; this has become a persistent feature in developed economies. The UK, like most other developed nations, actually has more qualified frontline staff today than it did pre-pandemic, which is not what you might think from the media or personal experience and still not enough to meet demand. More money and more people is not the solution to all of this, however well it plays as a tendentious political soundbite.

With this in mind, if one could invest into the technologies, products and services delivering those productivity gains, then surely that would feel like a safe space.

Now, where could you find a fund that does that?

We always appreciate the opportunity to interact with our investors directly and you can submit questions regarding the Trust at any time via:

shareholder_questions@bellevuehealthcaretrust.com

As ever, we will endeavour to respond in a timely fashion and we thank you for your continued support during these volatile months.

Paul Major and Brett Darke